You might want to read Part 1 first for this to make sense.

It turned out that assessment wasn’t the issue at the core. In reality there wasn’t a core, but a mishmash of understandings and histories and experiences that were getting in the way of common understandings. We were learning that when you ask people to do something they find challenging, there are times when holding their hands is the only way it’s going to get done, especially if they are so overwhelmed with everything else they’re doing that they don’t have the cognitive space for your particular priority.

I said before I’m a documentation-nerd. I’m also a curriculum-nerd. Love the stuff. It’s through our curriculum that we fulfil the contract we make with parents and students when they sign up to join our school. So it is absolutely vital that we look at our curriculum in painstaking detail, but it has to be written down before we can genuinely start that process.

Once you have built the skill, the headspace to be able to do this new task, and people have connected to the value of this thing you want them to do, you’ll find there’s more independent momentum, but this can take a long time (I’m talking years in some cases).

It was early in my second year at the school when a newly hired faculty member, DT, approached me. DT was also a curriculum-nerd and wanted to get involved. Whatever was needed. You might regret that offer, I replied, but took it up anyway. We started meeting each week, often just talking as we developed a common understanding of what needed to be done and how to go about it, and then moving into action. Many attempts failed, for one reason or another, but each time we learned something new, and progress was made.

We have now been working together on this project for 4 years, going into the 5th, and what started off as an ad-hoc talking group has grown and is now an officially sanctioned structural Whole School Curriculum Group for the coming year.

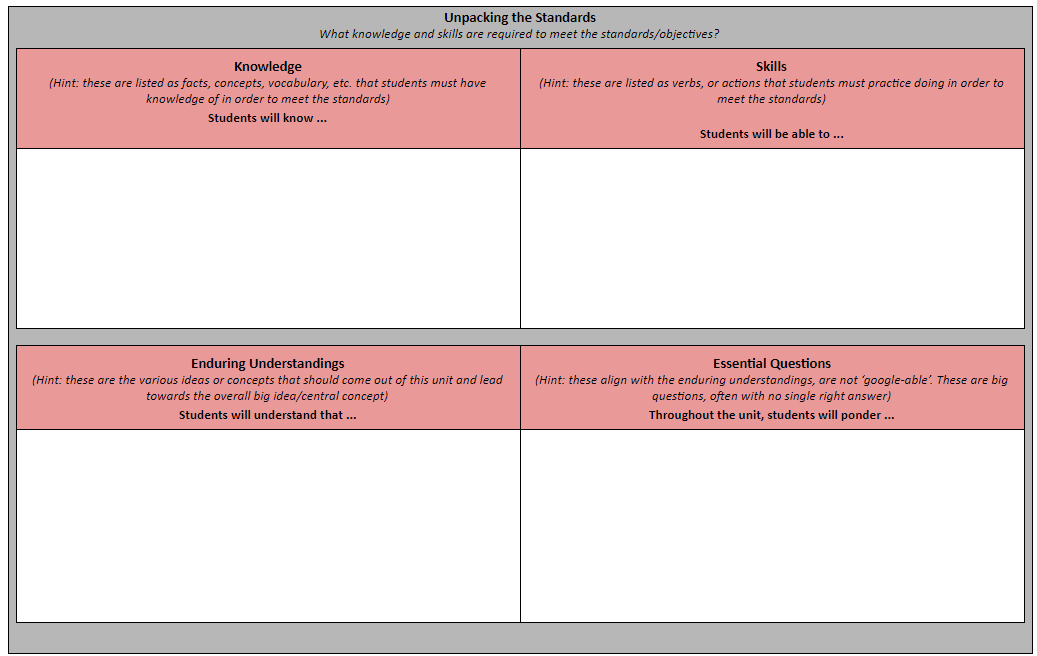

Back to the title of this post – Planning and the Planner. At some point around 2 years ago, DT and I had an epiphany. We had talked so much about the organisation of details on the planner. In particular, this section here:

We talked backwards and forwards about whether these should be presented as they are in this image, or whether we should switch them around:

We were trying to move practice away from a very content-focused, exam-driven approach, and encourage more big picture units with challenging inquiry.

As an aside, but an important one, I had worked with the MYP since 2005, and it was around 2008 that they introduce what was then The new MYP Unit Planner. We were obviously bothered by the change, why was it necessary, this is enough work as it is, etc. etc. But then I had another epiphany as I did the training course – there were fundamental differences to the way planning needed to take place and the Areas of Interaction, etc needed to be first and foremost, not an afterthought (as, honestly, they were a lot of the time previously). The reorganisation of the planner to put these areas first was deliberate and intentional, to force that change in the thinking processes.

So, I knew that the layout of the areas of a planner mattered, and DT and I bounced this particular section backwards and forwards. One week we’d make a decision, a couple of weeks later we would revisit it. Different conversations with different people would lead us to re-consider the prioritisation of these 4 sections: Knowledge, Skills, Enduring Understandings, and Essential Questions.

Until our epiphany. We were talking about the various needs of the different departments, and our recognition that each team would approach their planning from a different place. Lang & Lit, for instance, tended to be very skills-focused, and weren’t too bothered about the content. The Arts were also skills-focused, but liked to have a big idea. Mathematics and the Sciences, however were very, very driven by their content, and it was borderline impossible to even get a discussion going until we had identified the target knowledge and skills.

And then it clicked. What is the saying – the map is not the territory? Here was our version – “the planner is not the planning (process)”.

The best way I have found to think about this is the writing of a story. Think of a unit planner as a finished story. It’s been designed to be read from the beginning – start at the start and keep going through until you get to the end. However, story-writing doesn’t start with that first sentence – some may, but often there’ll be another starting place. Some stories were in fact inspired by their final sentence. Different authors will start from different places, and the same author may start from different inspirations and places from story to story.

We were dealing with a multitude of authors, grouped together into teams who often did have similarities in how they think (by the nature of their disciplines). There is no right place to start, but we have found that our language teachers very often start with a focus on the skills for instance, and mathematics teachers very often start with a focus on the concepts. Not always, but often enough.

Our epiphany was in recognising that the unit planner tells a completed story, but the planning process itself could start from anywhere, and our task when working with individuals/teams was to listen and work out where they felt the need to start from, and then help them to build from there. We would use the unit planner to document the outcome of the discussion, but we wouldn’t fill it in from start to finish. In fact, we usually make sure we have a large, hardcopy version of the planner, so that we can work non-linearly and messily, and then someone has the task afterwards of tidying it up and turning it into a digital draft.

This epiphany really was game-changing. All of a sudden, many of the apparent roadblocks disappeared. Instead of continuing trying to find ways to get people to think differently, some of whom had years of experience and expertise planning in a particular way, we could start from where they were and build from there. We would eventually end up with a whole load of beautifully written stories (aka units) but we’d take whatever journey had to be taken with each one, without having any preconceptions about the right place to start.

Think of it like building bridges. We knew where we needed to get to, but we had to reach out and help people build bridges from where they were.

I cannot overstate how fundamental this realisation – that the planner is not the planning process – has been to our work.